The residential and office building of the First General Accident Insurance Company (Erste allgemeine Unfallversicherungs-Gesellschaft) was built in 1916 on a large corner plot between Česká and Veselá Streets made available during Brno’s clearance and redevelopment.

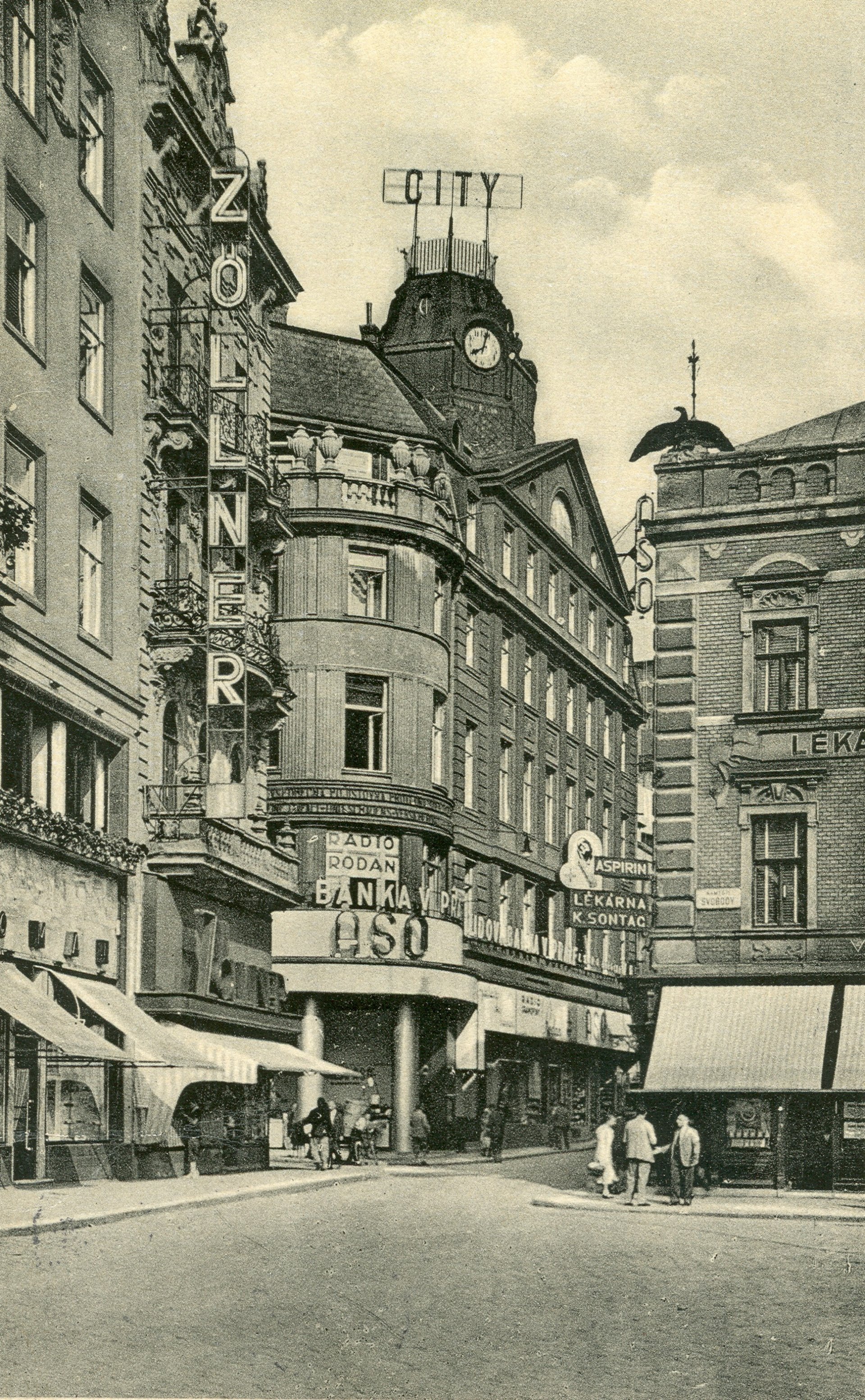

The complete original plans, which have been preserved at the Brno City Archives, were submitted to the city council for approval on 1 July 1915 and were signed by the Viennese architect Franz von Krauss, who designed a number of important buildings in Austria, Bohemia and Moravia. Krauss submitted two alternative facade designs. The chosen variant was characterized by a pair of rounded corners and a monumental triangular gable overlooking Česká Street. The design also included an intricately designed clock tower with viewing gallery at the centre of the building’s roof. The tower has not survived but can be seen in historical photographs.

The building’s elegant form follows the tradition of the Viennese Neo-Baroque style, updated through the use of simpler shapes and by integrating elements of geometric Viennese modernism. The facade of the three-wing, five-storey corner building is defined by its two rounded corners crowned by balcony terraces whose balustrades are lined with robust decorative vases. The building is divided horizontally into the commercial spaces and offices (basement, ground floor and mezzanine/first floor) and a residential upper part stretching form the second floor to the fourth floor in the mansard roof.

The basement was altered from the original design through a supplementary plan drafted by Brno architect Bohumír František Antonín Čermák dated 25 May 1916. Čermák also did the interior of the City-Bar, which opened in the building’s basement in late 1918. A large bar with a dance floor, in the evenings it hosted dance performances and a cabaret programme. The proprietor was Jan Nekvapil, who later managed the celebrated functionalist Savoy Café. The bar’s English name apparently confused customers, and so the following clarification appeared in the press: ‘The proprietor of the bar informs us that his establishment is and will continue to be Czech, and that the English poster only indicates that, as an institution of English public life, the bar will be run in an English manner and spirit.’ (Lidové noviny, 21 December 1918)

The American tradition of bars had arrived in Europe in the early 20th century, and these new establishments were a manifestation of modern, big-city cosmopolitanism. Adolf Loos’s American Bar in Vienna was a prime example of this trend. Bohumír Čermák designed several similar modern establishments around this time, both in Brno (the Old American Bar on the corner of Radnická Street and Zelný trh/Cabbage Market, 1912‒1913) and in Ostrava.

The City-Bar hosted a cabaret show put on by a group of young talented students, mostly active in Prague, who went by the name Červená sedma (Red Seven). Among the group’s performers who later achieved fame were Jaroslav Hašek, Eduard Bass, the Allan sisters, Bohuslav Martinů, Vlasta Burian and Karel Hašler. Since the cabaret boosted the bar’s attendance by attracting customers in the evening and not only during the busiest late-night hours, Nekvapil began to financially support the cabaret and even built a small stage and facilities for the actors. But the importation of Prague humour to Brno was not received with open arms, as evidenced by one contemporary newspaper report: ‘Červená sedma entered difficult terrain upon arriving in Brno, where Czech life is only just beginning to awaken after decades of being forcibly suppressed. Above all, where to find a proper audience for such an establishment among Brno’s Czech-speaking populace? Should it come from among the masses of working people and war-weary officials, or from those few members of the nouveau riche? The average Czech citizen of Brno, if he has the means, prefers a varied and comfortable life, the kind of entertainment that does not require him to think: wine bars, cafés, cinemas and variety shows. But a cabaret performance in which the audience co-creates? (…) how falsely modest our audience is, how painfully serious the men look when observing the ladies’ chorus line during some playful chanson by Miss Golwellová or Miss Filaunová. And finally, our audience is, in fact Austrian! Anyone who was not there would find it hard to imagine the bewildered and alarmed atmosphere that Dréman’s excellent caricature of the penultimate Habsburg evoked. Our audience has yet to learn to understand cabaret, but Červená sedma will also have to learn. If its mission is to be successful, it must not remain simply an extension of a Prague company. It is not enough to simply pass on a Prague joke to us, for it cannot work in a foreign environment.’ (Lidové noviny, 19 March 1919)

Červená sedma tried to adapt its programme to suit the local context, but after two seasons the troupe gave up trying to understand Brno’s audiences and focused its artistic efforts exclusively on Prague.

On 14 August 1919, not long after the City-Bar opened, the Kino Republika began showing films in the building’s basement cinema, which had an auditorium entered from the ground floor, two boxes and a gallery. Its interiors were designed by Čermák as well, with minor modifications in 1929.

The cinema was in operation until May 1935, when the building’s commercial spaces were acquired by the Olomouc company of Ander & Son. The company, which in the 1930s was building up a network of department stores throughout the country, established an ASO department store and cafeteria in this location, again designed by Čermák, who closely collaborated with the ASO company on several other buildings. In September 1959, the legendary Sputnik milk bar (see BAM, D118) opened in the building with an interior designed by the glassmaker and artist Jaroslav Brychta. It remained in operation until the 1990s. At present, the spacious commercial premises are occupied by various fashion chains.

Pavla Cenková